edited by Tim Curtis (@TpcurtisTim)

In 1986, a man named Warren Middleton published a book of essays by a number of contributors, many known paedophiles, that argued for the legalization of child sexual abuse. One of the authors who participated was our old friend Peter Tatchell, whom we discussed in my previous post. Middleton’s book was titled The Betrayal of Youth: Radical Perspectives on Childhood Sexuality, Intergenerational Sex, and the Social Oppression of Children and Young People.

What exactly is in this book? Who else contributed to it, and what did they say? How is it connected to the paedophiles’ rights movement of the 1970s, and how does that relate to Peter Tatchell’s current brand of activism?

This will be a deep dive into Betrayal of Youth’s contents, and its relationship with the notorious Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), a UK lobbying group founded in the 1970s to promote “paedophiles’ rights” to groom and to sexually abuse children. We will also discuss its contributors, their personal histories, and their beliefs on the subject of child sexual abuse.

It is my hope that this article will make very clear exactly what sort of person Peter Tatchell really is, and who his associates were during the height of his activism. Keep in mind that this book was published just 3 years after the Bermondsey by-election that made Tatchell well-known in the UK.

We begin our discussion of Betrayal of Youth with a look at the history of Warren Middleton, aka John Parratt, the book’s editor and publisher. Middleton was a prominent figure in the Paedophile Information Exchange, a pro-paedophilia UK lobbying group that existed from 1974-1984. The PIE advocated - as Tatchell has - to eliminate the age of consent. They also published multiple pro-paedophilia magazines, such as The Magpie.

Middleton was at one point the vice-chairman of the PIE, and while it had been disbanded by the time BoY was published, Middleton was clearly still very much dedicated to its mission: to abolish the age of consent and persuade the public to legalise the sexual abuse of children over the age of 4.

Middleton included a brief autobiographical sketch of himself in the beginning of the book, and it is worth noting that he includes a quote describing him as “one of the founding fathers of the paedophile movement in Britain.” Five years earlier, Middleton had been one of the defendants in the highly publicised trial of the PIE members for conspiracy, and he had been publicly known as a paedophile rights activist for years.

There is simply no way that Tatchell didn’t know who Middleton was, or what Middleton’s motives and bona fides were, when he agreed to contribute to the man’s book. Even if he had truly been clueless, however, even having just read the introduction, he would have known exactly what he was praising in his review.

Nor were Middleton’s activities confined to the 1980s. After changing his name at some point to John Parratt, he was charged in 2011 with helping to run an enormous ring of paedophiles whose members swapped thousands of images of child sexual abuse, along with computer games in which the goal was to rape as many young boys as one could.

Standing in the dock with him was a man called Stephen Freeman, whose name had once been Stephen Adrian Smith, a former Home Office official who was also a contributor to Betrayal of Youth - and who had for years run the PIE out of the London HQ of the Home Office itself.

Both men were found guilty of the 2011 charges of running a paedophile ring. Smith/Freeman in particular was noted to have had a collection of “vile and disgusting” CSAM that was one of the “largest and worst that officers had ever uncovered.”

(As of this writing, Smith/Freeman remains behind bars on an indefinite hold order, but his accomplice and erstwhile literary colleague Middleton/Parratt has been released.)

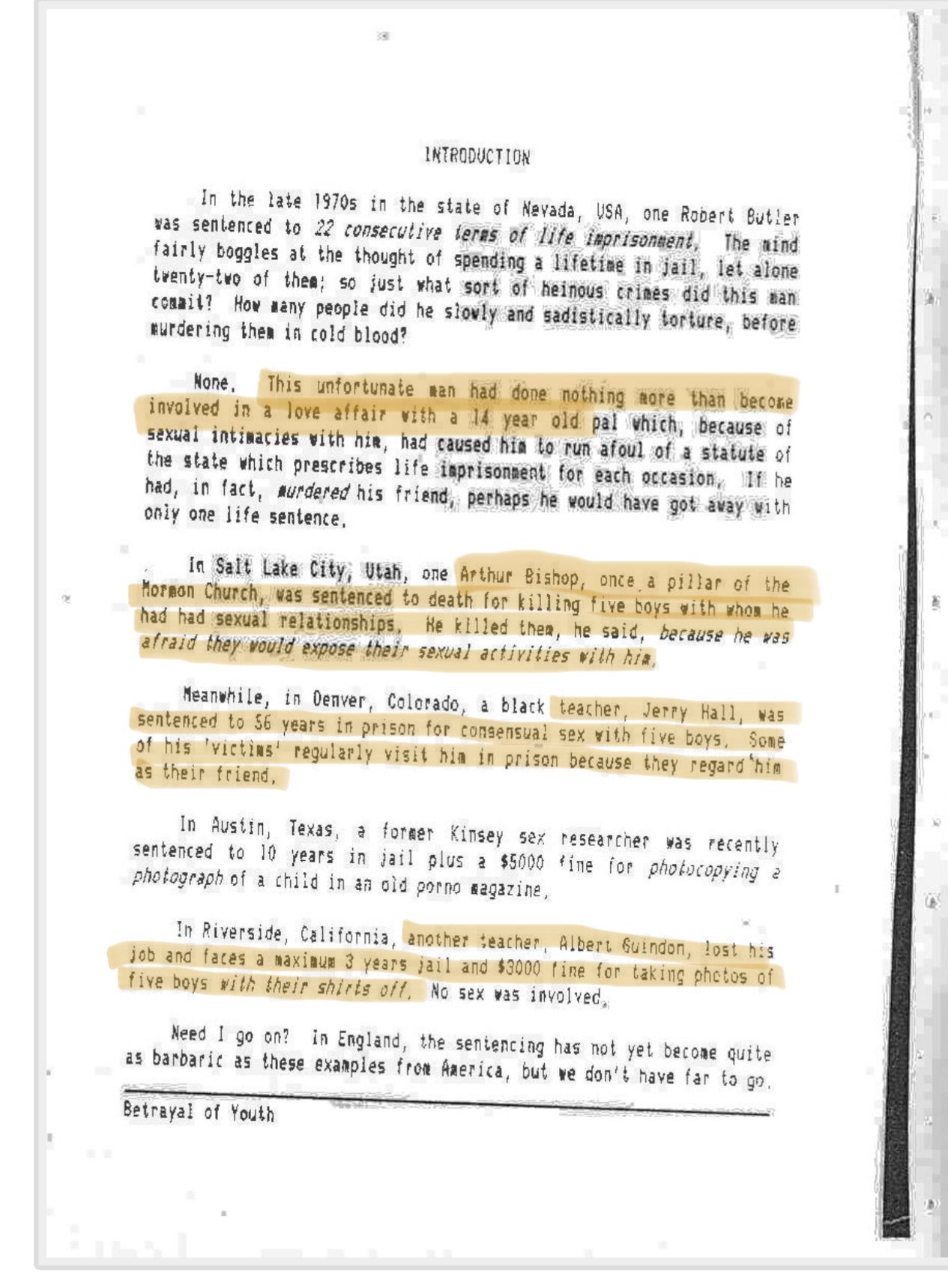

As stated earlier, even reading just the introduction would have told Tatchell exactly what sort of book he was reviewing. Middleton begins with a series of complaints about the fates of various paedophiles who were convicted and imprisoned for various sex offenses against children.

He specifically singles out one Arthur Bishop, a Mormon convicted of the rape/murder of 5 young boys, blatantly implying that the murders only happened because society led Bishop to fear exposure, and therefore he murdered the boys he had “sexual relationships” with.

Middleton also protests against the punishment of two teachers for child sex offenses, including one who groomed his victims so effectively that some still visited him in prison. He similarly objects to the 22 life sentences imposed upon a man named Robert Butler by the state of Nevada for a “love affair with a 14 year old pal”.

All this is just on the first page.

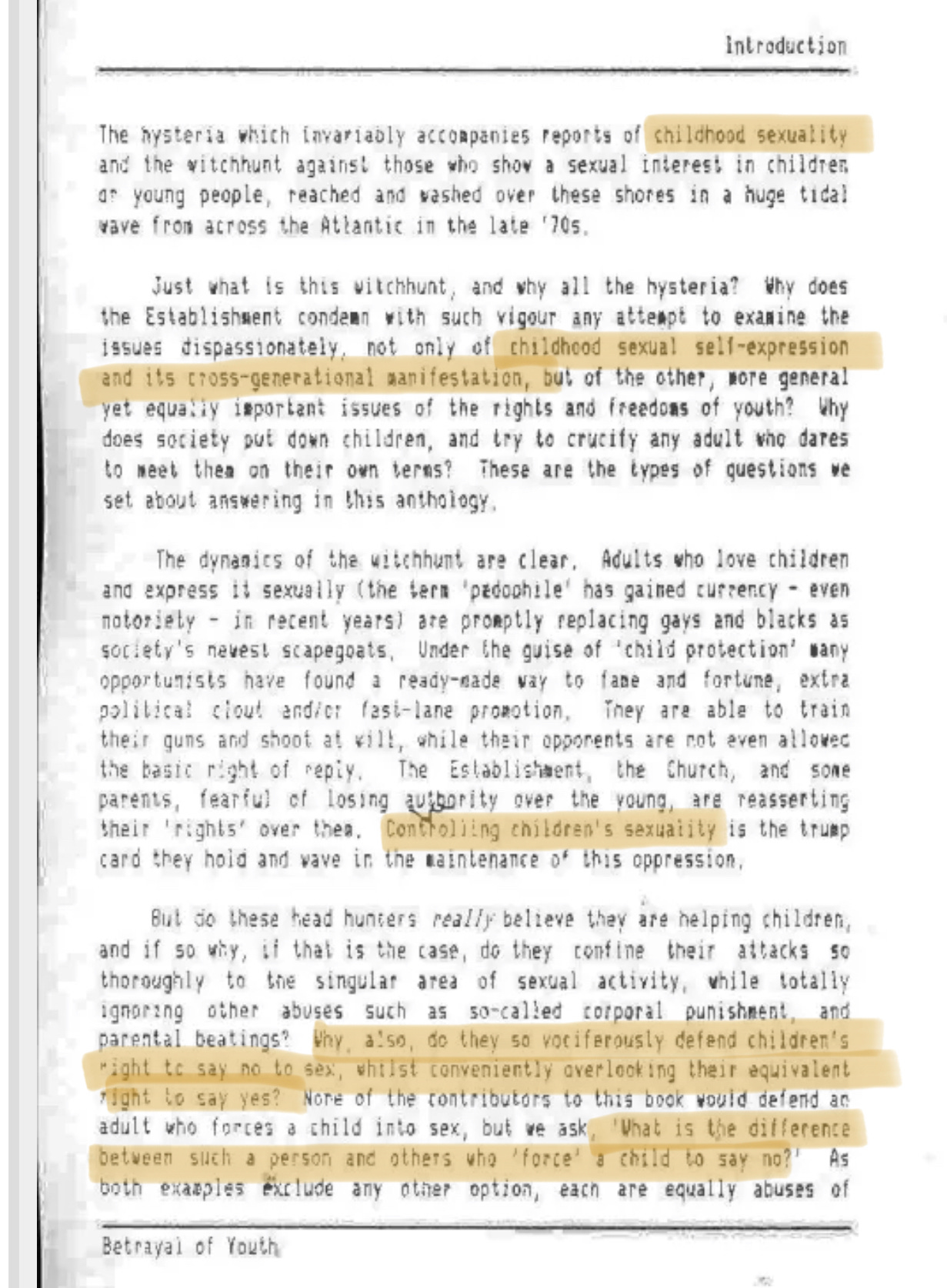

On the second page, Middleton goes into a long screed about how marginalized and abused “adults who love child sexually” are, claiming that child molesters are replacing gay people and Black people “as society’s newest scapegoats.”

He also makes repeated references to “childhood sexuality”, demonstrating a common type of behaviour among predators: that of putting the blame on the victim.

The child victim is recast as the sexual aggressor, the initiator of sexual contact, and the adult abuser is merely respecting “childhood sexual self-expression and its cross-generational manifestation” when he commits the abuse.

(Let me be very clear - even if a child does approach an adult for sex, it is still - and always - the adult’s responsibility to say NO.)

Most disturbingly of all, Middleton asks why child protection advocates are “vociferously defend[ing] a child’s right to say no to sex whilst conveniently overlooking their equivalent right to say yes” - that is, to be groomed into saying it.

We know - as Middleton and his contributors knew when they wrote their essays - that victims often rewrite events in their memories, taking upon themselves the onus for the abuse, and convincing themselves that they “enjoyed” it.

Some of these victims will go on to become offenders themselves, recreating their own trauma by abusing children as adults, convincing themselves that their victims “enjoy” the abuse in much the same way that they have convinced themselves of their own “enjoyment” when they were abused. Thus the horrors of child sexual abuse are passed down through the generations - with Middleton and his contributors cheering it on.

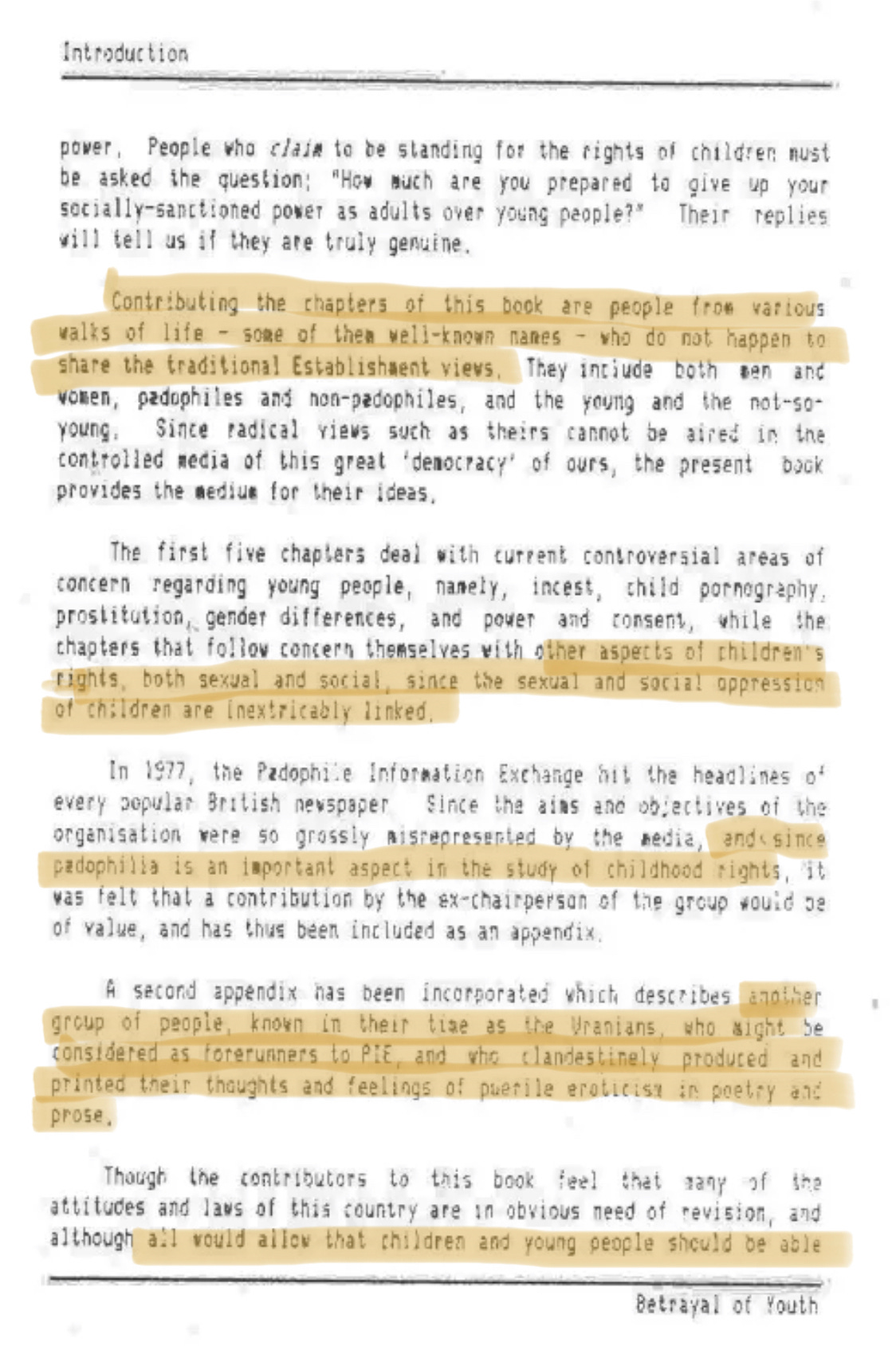

The third and fourth pages of the introduction give us a general introduction to the contributors, “some of them well-known names.” We’ll discuss them in more detail next.

Middleton also includes a brief defense of the PIE, and a quick summary of the book’s layout. He then takes time to assures us that all of his contributors, “paedophiles and non-paedophiles”, believe that “children and young people should be able to enjoy responsible self-expression”. Middleton has already been very clear as to what he means by that particular phrase: a child’s “right to say yes” to being sexually abused.

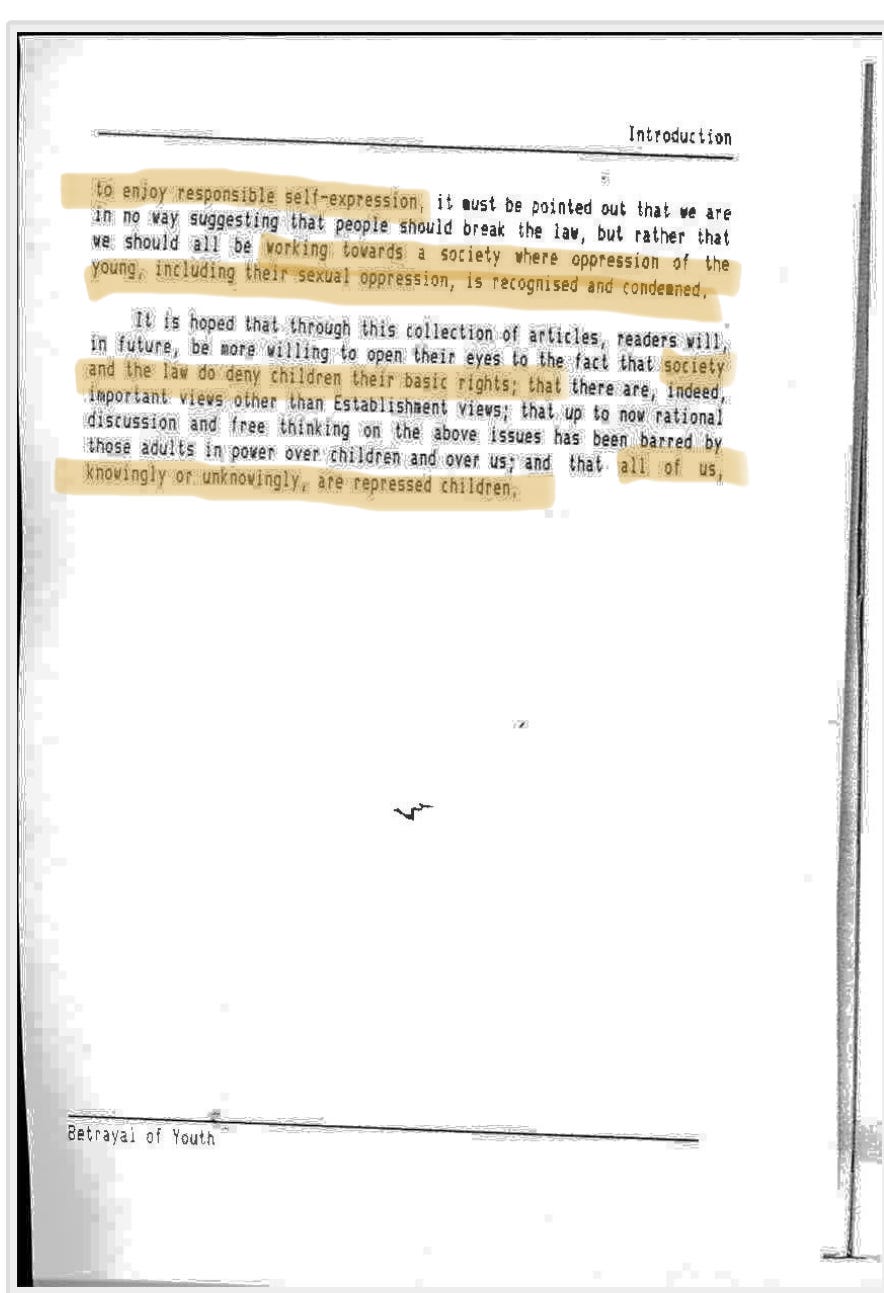

Middleton is also very clear on the aims behind the book and the aims of the PIE. He doesn’t want people to break the law; he wants the laws themselves changed, and thinks “we should all be working towards a society where oppression of the young, including their sexual oppression, is recognized and condemned.”

In other words, Middleton claims in his introduction that he - and his contributors - want a world where it is perfectly legal for adults to sexually abuse children, so long as they first groom them into “consenting.”

As we can see, the introduction to this book pulls no punches. It lays out its aims very clearly - and both Peter Tatchell’s review of and contribution to it, as well as his continued activism against age of consent laws, make it clear that he agrees with those goals.

END OF PART ONE